|

| Introduction |

| Poetry collecting |

| Lönnrot in Viena |

| Karelianism |

| Viena in the 1900's |

| Rune singers and collectors |

| Main page | Background | Villages | Revitalisation | Cultural tourism | Map | |

|

|

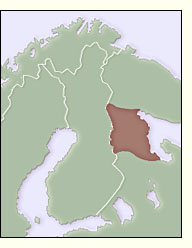

Geographically, Viena is the northernmost part of Russian Karelia.

Its borders are easy to define: it is that part of the czarist government

of Archangel west of the White Sea, an area constituting the district

of Kemi at the time. Today the same area comprises the districts

of Kalevala, Louhi, Kemi and Belomorsk, as well as the city of Kostomuksha. Finland also has villages which are part of the Viena cultural heritage; all three are located in the immediate vicinity of the border: Hietajärvi and Kuivajärvi in the municipality of Suomussalmi and Rimpi in the municipality of Kuhmo. These seemingly minor Viena villages have played a significant role in Finnish cultural history, for it was a poem recorded by Daniel Europaeus in Hietajärvi that prompted Elias Lönnrot to change the structure of the Kalevala. Rimpi, for its part, contributed significantly to the birth of Karelianism, an artistic movement that exerted a profound influence in many spheres of artistic endeavor in Finland in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

There are a number of reasons why the tradition of singing poems endured so long in Viena. Perhaps the principal factor was that literacy came to the region relatively late; it was not common until the 1920s. Before the introduction of a school system, libraries and communications, the oral tradition was a uniquely effective means of transmitting the cultural heritage and wisdom gained through experience from one generation to the next. Poem-singing, proverbs, fables and fairy-tales, or starinas, were the means by which that life experience was passed on. A second significant reason for the preservation of poem-singing in Viena was the remoteness of the villages. The region was on the periphery of Russia and was separated from Finland by a rather abrupt cultural divide. The first highway in the region, a road from Uhtua to Kemi in Viena, was not completed until 1929. Travel to the border villages in particular tended to be strenuous and complicated.

It is thus no accident that the best bardic villages are near the border, far from "development" but by no means strangers to culture. Today the bardic villages are defined as those villages in Viena which still exist or are scheduled for revitalization, and which have been sources of the poetry in the Kalevala and the Kanteletar or contributed to the birth of Karelianism. There are three such villages in modern Finland: Hietajärvi and Kuivajärvi in the municipality of Suomussalmi, and Rimpi, administratively a part of the city of Kuhmo. The bardic villages in Russian Karelia comprise Vuokkiniemi, Latvajärvi, Venehjärvi, Ponkalahti, Pirttilahti, Tšena, Tollonjoki, Akonlahti, Kontokki and Vuokinsalmi, all of which belong to the city of Kostomuksha; Uhtua, Vuonninen, Lonkka, Jyvöälahti, Haikola, Jyskyjärvi and Pistojärvi, located in the district of Kalevala; and Paanajärvi, situated in the district of Kemi. |

Viena

is the fabled heart of Karelia, and the single richest source of

the folk poetry which Elias Lönnrot used when he compiled the

Kalevala epic.

Viena

is the fabled heart of Karelia, and the single richest source of

the folk poetry which Elias Lönnrot used when he compiled the

Kalevala epic.

Various

periods have witnessed numerous disputes - some quite vehement -

about the ultimate origin of the "Kalevala poems". Settling

this issue is perhaps a secondary concern, however, for the fact

is that most of the poetry from which Elias Lönnrot created

the Kalevala came from Viena.

Various

periods have witnessed numerous disputes - some quite vehement -

about the ultimate origin of the "Kalevala poems". Settling

this issue is perhaps a secondary concern, however, for the fact

is that most of the poetry from which Elias Lönnrot created

the Kalevala came from Viena.